Pablo Picasso

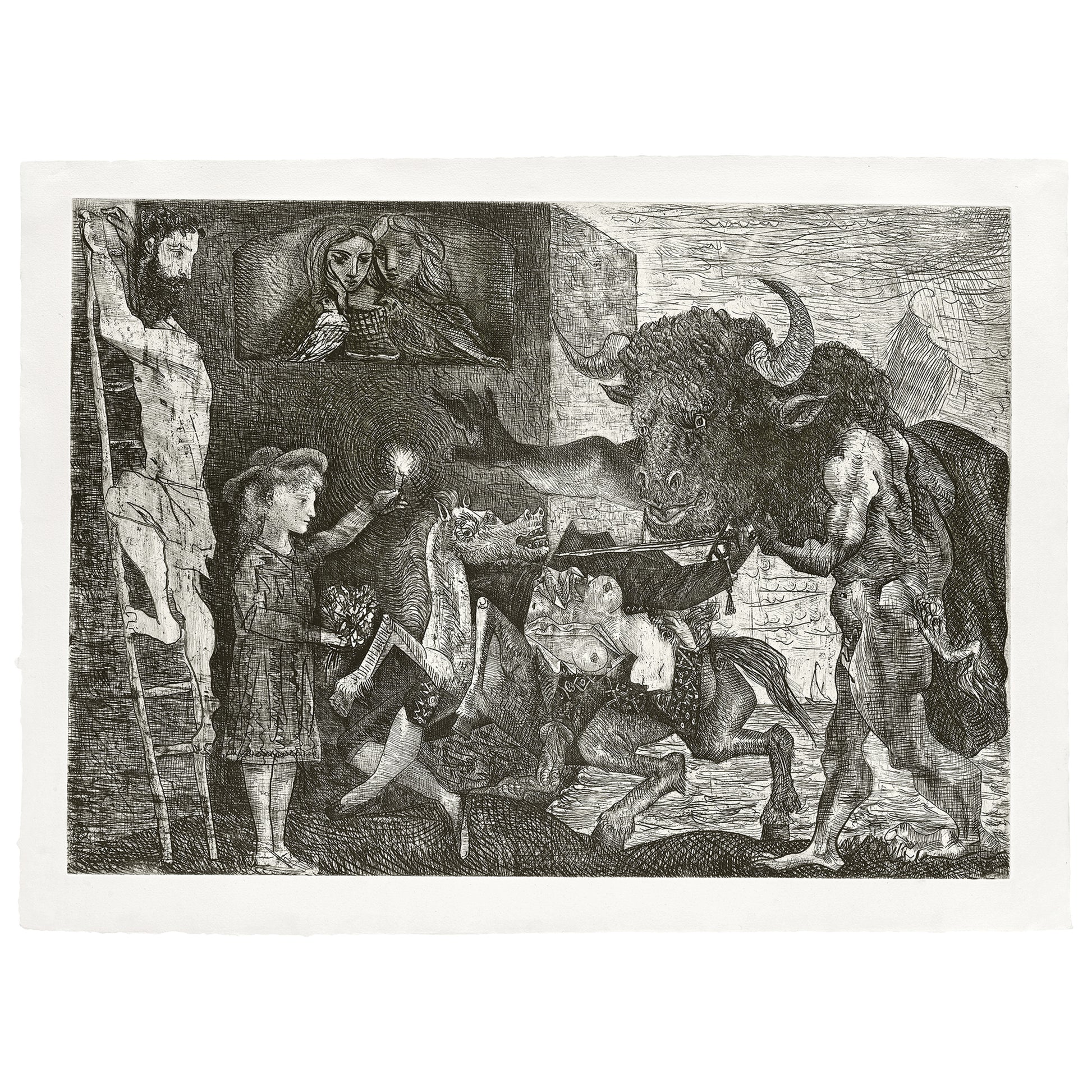

La Minotauromachie

etching and engraving with scraper on laid Montval paper with watermark, with full margins, deckle on all sides

image 49.8 x 69.4 cm (19 5/8 x 27 3/8 in.)

sheet 57.3 x 77.4 cm (22 1/2 x 30 1/2 in.)

Executed in 1935, this work is one of the 23 impressions from the artist’s estate, Baer’s seventh (final) state, published by Roger Lacourière, Paris and framed in its original condition.

Couldn't load pickup availability

Provenance

Provenance

Marina Picasso, France (by descent)

Private Collection, Europe (acquired directly from the above)

Phillips, London, 23 January 2020, lot 1

Acquired at the above sale by the present owner

Literature

Literature

Christian Zervos et al.,Picasso 1930-1935, Cahiers d’art, 1936, p. 85

Paul Eluard, À Pablo Picasso, Geneva & Paris, 1944, pl. 102

Alfred Barr, Jr.,Picasso. Fifty Years of his Art, Museum of Modern Art, New York,1946

Daniel E. Schneider, The Painting of Pablo Picasso: A Psychoanalytic Study, College Art Journal 7, 1947-48, pp. 81-95

Curt G. Seckel, Picasso und die Insel des Minotaurus, Betrachtung über eine Raiderung, Das Kunstwerk und das Schöne Heim 4, vol. 5, 1950, pp. 26-29

Wilhelm Boeck, Picasso, Stuttgart, 1955, p. 401

Vicente Marrero Suárez,Picasso y el Toro, Madrid, 1956

Curt G. Seckel, Die Minotauromachie. Bildehafte Meditation aus einem Schicksalsjahr Picassos, Zeitwende, Die Neue Furche 30, 1959, pp. 245-253

Jan Runnquist, Minotauros, En Studie i Förhållandet Mellan Ikonografi och Form I Picassos Konst, 1900-1937, Stockholm, 1959

Sir Herbert Edward Read,The Form of Things Unknown, Essays Towards an Aesthetic Philosophy, New York, 1960, pp. 64-75

Otto J. Brendel, Classic and Non-Classic Elements in Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, Bloomington, Indiana, 1962, pp. 121-162

Albert E. Elsen, Purposes of Art, New York, 1962, pp. 388-405

Alfred Scheidegger, Der Monotauros, Dreissig graphische Blätter von Pablo Picasso, Frankfurt, 1963

Carla Gottlieb, The Meaning of Bull and Horse in Guernica, Art Journal 24, 1964-65, pp. 106-112

Georges Bloch, Catalogue de l'oeuvre gravé et lithographié 1904-1967, Bern, 1968, p. 286, no. 288

Anthony Blunt,Picasso’s Guernica (The Whidden Lectures for 1966), New York, Toronto, 1969

André Fermigier, Picasso, Paris, 1969

Martin Ries, Picasso and the Myth of the Minotaur, Art Journal 32, 1972-73, pp. 142-145

Rui Mário Goncalves, Guernica e os mitos, Coloquio Artes No. 16, 1973, pp. 18-25

Curt G. Seckel, Meister der Graphik – Picassos Wege zur Symbolik der Minotauromachie, Die Kunst und das Schöne Heim 85, 1973, pp. 289-296

Herschel Browning Chipp, Guernica: Love, War, and the Bullfight, Art Journal 33, 1973-74, pp. 100-115

Jürgen Thimme, Picasso und die Antike, Badisches Landesmuseum, 1974

Francis Ponge, Pierre Descargues and Edward Quinn, Picasso, Paris, 1974, p. 212

Timothy Hilton,Picasso, London, 1975, no. 166, p. 225

Mary Mathews Gedo, Art as Autobiography, Chicago & London, 1980

Marc Le Bot, Minotauromachie, L’Arc, Revue trimestrielle, Aix-en-Provence, 1981, pp. 30-34

Jürgen Thimme, Pablo Picasso’s ‘Minotauromachie’, Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen, 1981, pp. 105-122

Lydia Gasman, Mystery, Magic and Love in Picasso, 1925-1938, New York, 1981

Sebastian Goeppert and Herma C. Goeppert-Frank,Pablo Picasso’s ‘Minotauromachie’, 1981, various

Marie-Laure Bernadac, La Minotauromachie, 1935, French Academy in Rome, 1982

Gloria K. Fiero, Picasso’s Minotaur, Art International 26, 1983, pp. 20-30

Brigitte Baer, Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection, Dallas Museum of Art, 1983, pp. 94-97

Brigitte Baer and Bernhard Geiser,Picasso Peintre-Graveur, Bern, 1986, vol. III, p. 17, no. 573

Sebastian Goeppert and Herma C. Goeppert-Frank, Minotauromachy by Pablo Picasso, Geneva, 1987

Brigitte Baer and Bernhard Geiser,Picasso Peintre-Graveur, Bern, 1996, addendum to vols. I-VII, pp. 28-32

Brigitte Léal, Christine Piot and Marie-Laure Bernadac, The Ultimate Picasso, New York, 2000, no. 711, p. 292

Kathleen Brunner, Picasso Rewriting Picasso, London, 2004, pp. 8 and 20-21

Emmanuel Benador, Picasso Printmaker: A Perpetual Metamorphosis, 2005, no. 32

Picasso. Toros, Museo Picasso, Malaga, 2005, p. 84

Stephen Coppel, Picasso Prints – The Vollard Suite, The British Museum, London, 2012, p. 37

Condition Report

Condition Report

Available upon request

Please fill out the below form and you will receive a response from a Phillips Specialist shortly.

Essay

Essay

In the Parisian studio of master printer Roger Lacourière, Pablo Picasso began on March 23rd, 1935 to engrave a large copper plate. This plate became one of the most important graphic works of the 20th Century and the pinnacle of Picasso’s printmaking oeuvre:La Minotauromachie. Technically brilliant and visually complex,La Minotauromachieis an intimate and autobiographical allegory rife with personal symbolism. It has been understood as the illustration of a private ethical battle as well as a universal parable of good and evil, violence and innocence, suffering and salvation.

La Minotauromachieis the culmination of a near frenzied period of printmaking as Picasso was completing his most important group of etchingsLa Suite Vollard(1930-1937), comprising one hundred images. It also coincided with, or was perhaps determined by, a time of strife that the artist later described as “la pire époque de ma vie” (“the worst period of my life”). His wife, the Russian ballerina Olga Khokhlova was on the verge of leaving him after discovering that his much younger mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter was pregnant. The significant turbulence in Picasso’s personal life was the backdrop to him working directly on plates and indulging in the physical act of complex, visceral mark-making that was driven by an urgent and cathartic need to create.

Through this lens of Picasso’s guilt and frustration with his personal life, the figure of the Minotaur grew. Triggered by a commission to provide a cover illustration for the newly launched Surrealist magazineMinotaure, Picasso’s alter-ego figure of the Minotaur appears throughout the etching seriesLa Suite Vollard, which directly precededLa Minotauromachie. This motif represents the dark centre of man’s violent, irrational and lustful desires. A mythological beast that is at once the monster within, but also the fighting bull of Picasso’s native Spain, whose power, pride and ferocity corresponds with the artist’s own character.

InLa Minotauromachiealmost half of the printed image is dedicated to the towering figure of the Minotaur whose arm is flung forward, reaching towards a lit candle held aloft in the hand of a young girl who holds a bouquet of flowers in the other. Between their frozen confrontation, a mare horse and torera (female bullfighter) are paired together. The shrieking mare eyes the Minotaur in terror attempting to flee the danger he represents, but she is mortally wounded - her stomach has been gouged with her entrails flowing out. She exudes an abject fear that starkly contrasts with the serene countenance of the female bullfighter, resting placidly on the mare’s back with her breasts exposed. Her features, just as those of all four of the female figures in the print, are those of Marie-Thérèse and her stomach appears swollen with child. Three attendant figures observe the catastrophic scene below: two young women peering down as though from a theatre box, and a bearded Christ-like figure with the face of Picasso who escapes via a ladder, but is unable to resist looking over his shoulder.

According to legend, the Minotaur had the power to see where others could not, because his eyes were accustomed to the darkness of the labyrinth. This opposition between light and dark divides the composition ofLa Minotauromachieboth formally and conceptually into two planes. The unbridled impulses shared by Picasso and the mythical Minotaur: desire, guilt and revenge, are sublimated before the supine figure of Marie-Thérèse who, in her pregnancy, literally embodies the consequences of Picasso’s adultery. Minotaur and torera are halted by the young iteration of Marie-Thérèse who holds a radiating candle and bouquet of flowers as a paradigm of innocence, truth and virtue - the two visions of Picasso’s lover combine to demonstrate her past and future, irrevocably changed through the artist’s intervention.

The mythical Minotaur becomes the physical embodiment of Picasso’s and by extension all of mankind’s fundamentally split personality: torn between conscience, humanity, civility and the underlying animal instinct that begets lust and violence. The imaginary Minotaur lives on the boundary of human experience. Half-man half-monster he has not yet transformed into the dehumanised bull ofGuernica, Picasso’s magnum opus painted two years later in response to the Spanish Civil War and the ensuing tyranny of Fascism. In this epic political work Picasso’s iconic Minotaur motif is no longer a symbol of mortal sin, but a full rendering of the malign power of war.

More Details

More Details

"Know Your Client" (KYC) Verification Required

-

About PhillipsX

Explore NowPhillipsX is a dynamic selling exhibition platform operated by the global Private Sales team at Phillips, the destination for international collectors to buy and sell the world’s most important Modern and Contemporary art, design, and luxury items.

-

Contact Us

Enquire NowQuestions? Click the button below to request an exhibition catalogue or to learn more about a specific work on offer.